If – like me – you missed this fascinating 2023 study on the development of prehistoric cannabis cultigens by Rita Dal Martello et al., you can download the pdf here: Cannabis differentiation and Haimenkou.

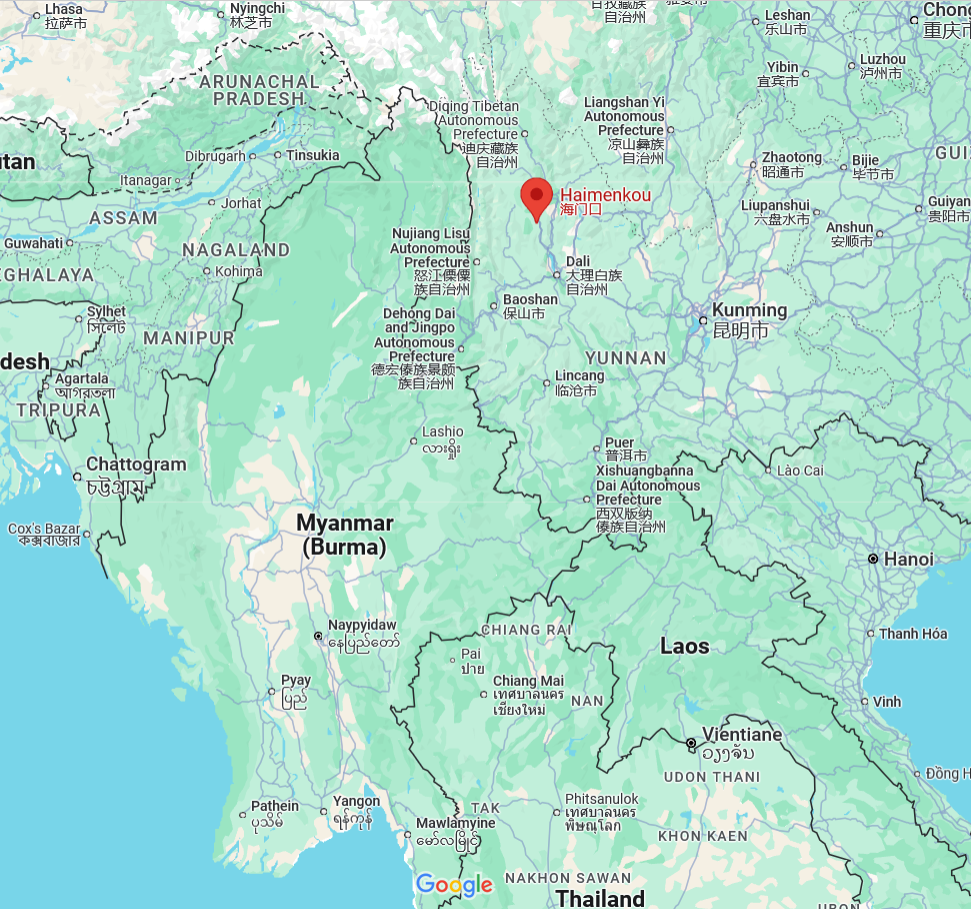

The authors examine archaeological cannabis seeds with the aim of illuminating the early development of the crop into distinct drug-type and fibre-type domesticates. Their idea is that fibre- and grain-type domesticates can be distinguished from drug-type based on seed morphology. By comparing known archaeological and modern samples, they analyse over 800 cannabis seeds dated to between 1650 and 400 BCE that were excavated from a site named Haimenkou to the north of Dali, Yunnan (Southwest China).

Haimenkou is located close to “the core area of the 1st millennium BCE polity of the Dian”, which is closely linked to Tai peoples such as the Shan and Lao, who may have originated in or near the Dian kingdom before migrating to regions such as Burma, Laos, and Northeast India. The region was likewise an area in which Tibeto-Burmans settled and through which they too migrated south into Southeast Asia and west into Northeast India.

Because the sizes of the analyzed cannabis seeds “mostly plot in the range of overlapping psychoactive/fibre types”, the authors suggest that “the cannabis assemblage from Haimenkou is indicative of a crop beginning to undergo evolution from its early domesticated form towards a diversified crop specialized for alternative uses, including larger oilseed/fibre adapted varieties” – and of course, drug varieties.

For researchers keen to investigate the seed morphology of drug-type landraces in closer detail, there’s extensive data on seed weights and shapes here, including over 140 accessions mostly from Central, South, and Southeast Asia that were collected by The Real Seed Company. Among them are ganja landraces from Laos, Isan, Mae Hong Son, and Burma, as well as Manipur and Orissa, and a hemp landrace from Northeast Laos. The site is best viewed on a laptop.

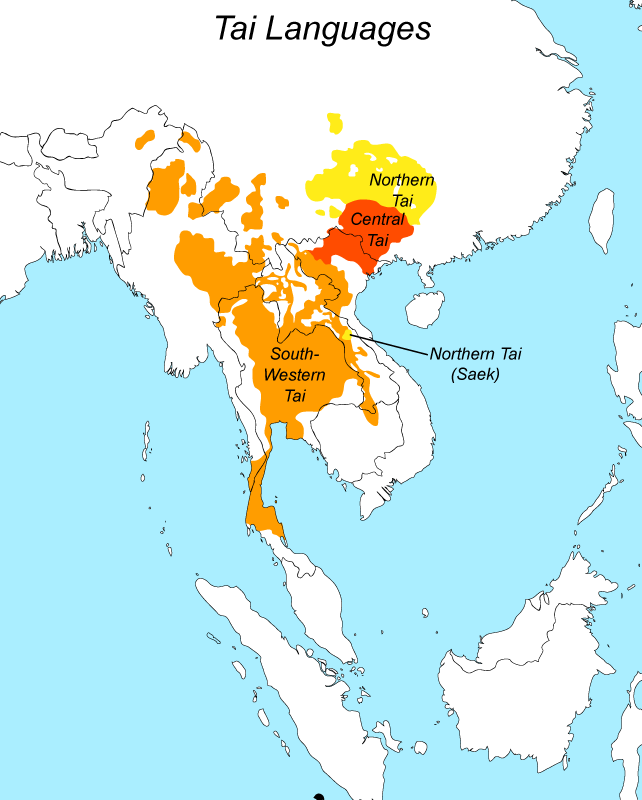

Yunnan itself is a region where cannabis is currently cultivated as a fibre and grain crop (‘hemp’), and also occurs as a widespread weed in feral forms, possibly even as a truly wild plant. Immediately to Yunnan’s south and west are ethnically Tai regions such as Laos, Thailand, and Shan State where the most common form of the cannabis crop has historically been drug-type cannabis – i.e., ganja. Hemp cultivation can be found among non-Tai highland ethnic groups such as the Lanten and Hmong, but these communities migrated into Laos and Thailand relatively recently. Among South-Western Tai speakers, the cannabis crop is ganja.

In the bigger picture, Yunnan was favoured by the cannabis breeder David Watson (Skunkman) as the most likely origin of the cannabis plant itself, an opinion he arrived at after growing a wide range of landraces from China, Thailand, and Afghanistan and noticing how their aromas and other traits all pointed to Yunnan as their likely shared origin. An increasing number of studies using genomics and fossil pollen suggest that at least his hunch as to the origin of the species was broadly correct and point to the contiguous area of Tibet as being where Cannabis sativa L. probably speciated from the hop tens of millions of years ago. Rob Clarke and Mark Merlin advocate specifically for the Hengduan Mountains.

But what’s likely to be new and most fascinating about the present study for folks reading here is how it sheds light on a likely course of development for the ancient ancestors of Tai landraces, particularly the drug-type forms now cultivated for ganja in Thailand, Laos, and areas of Burma like Shan State.

Cultivation of drug-type landraces is associated with the South-Western Tai area, particularly along the Mekong River in Isan and Laos, but also within the Mekong basin in Shan areas of Burma.

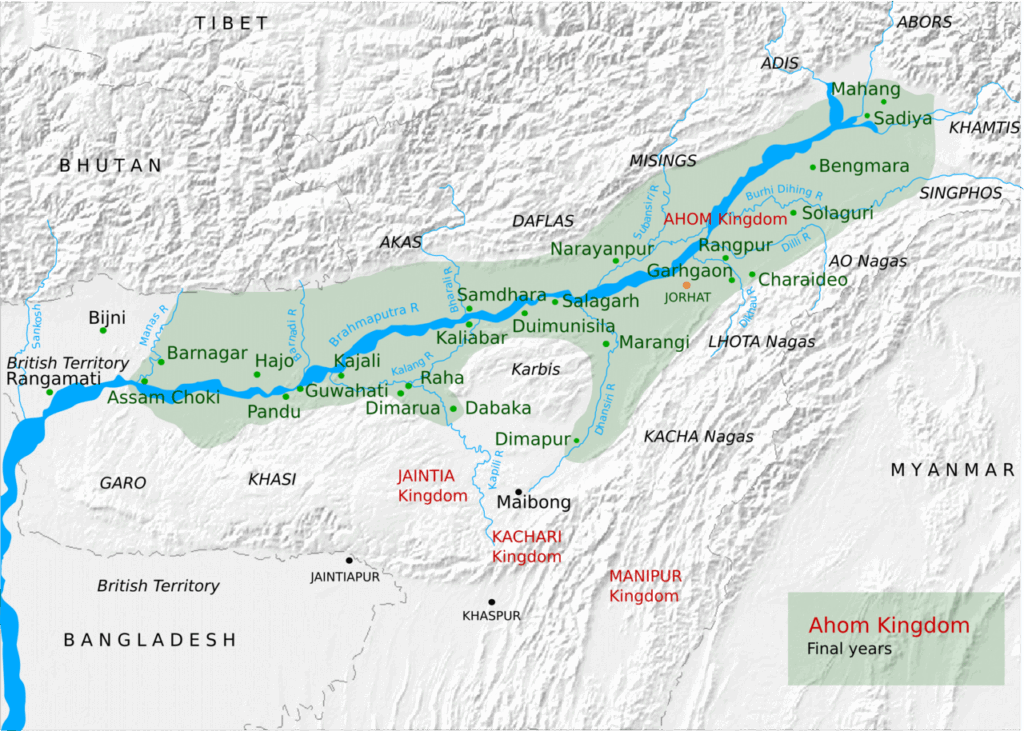

In addition, to my mind, the study’s insights raise the compelling possibility that a Tai kingdom that ruled much of what’s now Northeast India may have played a role in introducing drug-type cannabis to the Sanskritic cultures of medieval India – through Assam and Manipur and into regions that would later become historic ganja cultivation centres, most notably Bengal and Odisha.

The kingdom in question is the Tai kingdom of Ahom, which over the course of its history controlled territory along the Brahmaputra River from the frontiers of Tibet and Upper Burma around what’s now Arunachal Pradesh up to the borders of Bengal, ruling from around 1228 to 1826 CE. The first two centuries of the Ahom Kingdom overlap with the ‘Pax Mongolica’, when the Mongol Yuan Dynasty ruled China and overland ‘Southern Silk Road’ trade routes linked Yunnan through Northeast India and Bengal to the Indian Ocean. This period saw increasing connectivity between the Tai and Indic worlds and coincides closely with the earliest definite references to cannabis drugs in Sanskit texts from South Asia, particularly the period in which they first become really prevalent – i.e., during the 13th Century.

For folks raising an eyebrow at that idea, a scholarly look at the question of when exactly (1) drug-type cannabis arrived in India and (2) first shows up in Sanskrit literature (two separate questions, note) can be found in the work of Gerrit Jan Meulenbeld. Along with most Indian scholars of Ayurveda, Meulenbeld argues that cannabis drugs only unambiguously appear in Indian medical and religious literature during India’s Persianate era, occurring no earlier than about 1000 CE and under the grammatically feminine name bhaṅgā (भङ्गा). In this view, the earliest definitive reference to cannabis as an ‘intoxicating’ substance is generally agreed to be by Vaṅgasena, an important author in the traditions of Ayurveda, who was located in Bengal and flourished around 1050 – 1100 CE. That medieval date is likely to strike some aficionados as implausibly late and inspire talk of the Vedas and so forth. But the contention of these academics is that although the masculine and neuter forms ‘bhaṅga’ (भङ्ग) such as are found in the Atharvaveda or Pali canon – texts from or rooted in the Iron Age – may perhaps refer to fibre-type cannabis (‘hemp’), they could just as likely be names for any number of other things or plants. Among Sanskritists, the prevailing orthodoxy remains that drug-type cannabis, like opium, was probably introduced into India with Islam, particularly with Persianate forms of Islam from Central Asia such as blossomed in the Samanid Empire (819 – 999 CE).

In the contrasting and much more expansive view of one of the authors of this 2023 paper on Haimenkou, the archaeobotanist Professor Dorian Fuller, it’s around the Late Harappan Horizon (3900 – 3500 BCE) that “cannabis comes to India […] as part of the “Chinese horizon”, which is really just piece meal adoption of various things coming in via Central Asia including crops and technologies (harvest knives) from China, peaches, apricots, millets, japonica rice.” It’s plausible, Fuller notes, that cannabis at this date was also “already utilized from wild populations in the Himalayas.” That would place the earliest stirrings of drug-type cannabis in South Asia about five thousand years earlier than reckoned by Meulenbeld – at least….

Where and when drug-type domesticates may have developed within South Asia and the Indian and Nepali Himalaya long prior to the Muslim era is looked at in this 2023 study and others by Fuller such as Between China and South Asia. That development may have involved cannabis specializing from a multipurpose crop to a drug crop (i.e., Indic – as opposed to Tai – ganja landraces) in regions such as the Kathmandu Valley. As implied by Dal Martello’s study, among the earliest cannabis domesticates were surely multipurpose, and it’s notable that multipurpose landraces are to this day the main type of cannabis cultivated in the Indian and Nepali Himalaya. Very tall and typically with good bast fibre and large oily seeds, multipurpose Himalayan landraces produce sufficient THC for use as charas or edibles. They show close relatedness to South Asian ganja landraces. (Tangentially, cannabis was described as a multipurpose crop by the agronomist Ibn Wahshiyya, who died c. 930 CE in eastern Iraq, and a multipurpose landrace named ‘Smyrna’ was common throughout the late Ottoman Empire.) Suffice to say, what we’re probably looking at for Indic cannabis culture is a picture of multiple domestications and diffusions within and without the subcontinent. In other words, most probably, specialized drug-type crops developed within South Asia and were introduced to South Asia from across its frontiers to the northwest, north, and northeast. By the medieval era, peaks of connectivity across Eurasia established with the Arab Conquests and Pax Mongolica may have accelerated the dispseral, popularity, and visibility of drug-type cannabis from ancient centres of domestication such as Central Asia (Turko-Persianate / Samanid) and Southeast Asia (Tai / Ahom).

To reconcile the sharply different views of Meulenbeld and Fuller, simply bear in mind that the absence of cannabis drugs from Sanskrit literature is not the same thing as their absence from India altogether, as noted by Professor James McHugh. We should probably treat Indian medical and religious texts as a very unreliable set of sensors for detecting the presence or absence of cannabis, not least among the many non-Sanskritic cultures in and around the subcontinent. Cannabis was certainly about in South Asia in some form prior to 1000 CE, even if people writing in Sanskrit weren’t writing about it, whether because they hadn’t encountered it or didn’t think it was worth remarking upon. What seems likely is that prior to 1000 CE, its use as a drug in South Asia was confined to various geographic and cultural margins of the Sanskrit culture zone. Then, around the 13th Century, things really get going, and you start seeing cannabis drugs show up everywhere in Indian literature in a big way, at least in part – I suspect – due to increased connectivity with the Tai world to India’s northeast.

Over a century ago, Nikolai Vavilov proposed that cannabis was very likely independently domesticated at multiple times and places across Eurasia, an opinion still shared by most experts. Dal Martello et al.’s interpretation of Haimenkou provides a plausible origin story for this type of “both… and…” scenario, one where Tai cultures also introduce drug-type cannabis into the Sanskritic culture zone of medieval India by a highly frictional overland route through Zomia and Assam during the medieval era. In this way, the crops and products that come to be known as bhaṅgā and gañjā (गञ्जा) emerge from across India’s Central Asian mountain frontiers to the north, west, and east: from the Himalaya, through the passes of the Hindu Kush with Indo-Iranians and Islam, and along the course of the Brahmaputra from the Tai mueang that were expanding out of the foothills of the Southeast Asian Massif in the early second millennium. If so, then the literature of the Ahom Kingdom might have something to tell us about the eastern chapters of this history.

Broadly contemporary with this imagined expansion of Ahom ganja culture through Assam is a crucial text of Indian cannabis culture which was compiled sometime between the 12th and 15th centuries at Srisailam, a Shakta–Shaiva temple complex 100 miles inland from the Coromandel Coast in the jungle highlands of what’s now Andhra Pradesh. This is the Ānandakanda or ‘Root of Bliss’, an alchemical compendium that expounds in great detail on the characteristics, effects, and uses of cannabis, and sets out techniques for producing potent, resinous ganja, strongly implying its authors were applying the ‘sinsemilla technique’ of roguing out male plants.

The compilers of the Ānandakanda were Nath Shaiva alchemists whose metier necessitated engaging with trade across the frontiers of India from Central Asia, the Himalaya, and Indian Ocean in order to acquire commodities such as mercury, coral, spices, aromatics, and precious metals. Though most closely associated with Bengal, the siddha milieu of these Shakta yogi–pharmacists involved a world of power places and temples that extended from Sindh and Peshawar to Sumatra and Assam. This linked the Nath alchemists into trade networks such as those of Persian Muslims, Sogdian Zoroastrians, and Tibetans, and inevitably also with Ahom Tai culture at sites such as Kamakhya in Assam. Notably, Kamakhya is a very important Shakta site, and Shaktism was the Tantric tradition to embrace cannabis in a big way, not least in Bengal, Assam, and further south at Srisailam.

All this interconnectedness across the subcontinent and its frontiers is why the cosmopolitan culture of the Nath siddhas at the particular node of India’s ‘economy of the sacred’ in 15th century Srisailam could produce a text such as the Ānandakanda – just as ganja was on the brink of becoming a truly global crop and commodity. How maritime trade across the Bay of Bengal during the Age of Sail (mid-C16 to mid-C19) may have further shaped the cannabis of the East Indies is set out at the introduction for our accessions from Southeast Asia.

Preliminary genome trees suggest particularly close genetic connections between southern Chinese landraces, Himalayan drug-type landraces, and the ganja landraces of South Asia and Southeast Asia. To expand on the Haimenkou hypothesis, the earliest Indian lineages within this grouping perhaps traced two paths: one from Yunnan through Tibet into the Nepali Himalaya, the other overland to Northeast India, likely with Tibeto-Burmans or perhaps in the latter case also with proto-Tais. The Tai sister lineage diverged on a southward route from Yunnan along the Mekong River basin to specialise as a drug crop in the riverside villages of Burma, Laos, and Isan.

But it remains to be seen how closely botanical reality will prove to align with the idea that they underwent a significant diffusion westward across Assam and the Bay of Bengal. In the Age of Sail, maritime connectivity is likely to be stronger – i.e., it is much easier for ganja to move by sea than through jungle highlands. But it could be we’re looking at overland connectivity moving specialized drug-type cannabis from Yunnan and Nepal and into South Asia some two millennia prior.

So far, it still appears like Vavilov probably did get it right: for drug cannabis, what seems likely is that multiple independent domestications and specializations in and around China and Central Asia created several distinct landrace groups, closely defined by product and region, with some interesting genetic relationships and overlaps that could yet further illuminate the outlines of the speculative history put together here. To begin, however, the genomics work involves identifying ‘pure’ genotypes (i.e., free of signs of hybridization) for each major group or class of landraces and feral populations, and then proceeds to the stage of testing how related other samples are to those relatively ‘pure’ genotypes. The hope is that, ultimately, genomics will illuminate the story of this crop and give us a picture of how we and cannabis really did get here together.