There’s a far older name for seedless bud than ‘sinsemilla’, namely ‘ganja’.

To be clear, ‘ganja’ is not a catch-all term for any type of cannabis drug – though aficionados in the west may sometimes misuse it that way. Ganja is in fact a specific product produced from product-specific domesticates, plants that we could call ‘tropical drug-type landraces’ – or to use the popular jargon term, authentic ‘Sativas’.

To get this doubly clear – ‘Sativas’ as used here in this post definitely does not mean the stuff called ‘Sativa’ at your local dispensary, cannabis club, or coffee shop.

‘Sativas’ here means the pristine landraces that can still be found in regions of the tropics such as Laos, Orissa, and Burma. That is, in those few places where these ancient cannabis domesticates have not yet been brought to the brink of extinction.

And for the record, what’s forcing cannabis landraces to extinction is not crop eradication but introgression with the modern Dutch and American Indica–Sativa hybrids introduced by western backpackers and rich Asian city kids.

So what we’re talking about when we talk about ganja is sinsemilla and the type of landrace used to produce it for hundreds of years in its historic centre of origin – the areas of Asia in and around the Bay of Bengal.

The ‘sinsemilla technique’ was very likely already in use around the 15th Century in Southeast India, as strongly implied in a massive Sanskrit alchemical compendium named the Ānandakanda (आनन्दकन्द) or ‘Root of Bliss’. The likely site of the Ānandakanda’s compilation is some 180 miles inland from the Bay of Bengal at the highland jungle temple complex of Srisailam, in what’s now Andhra Pradesh, Southeast India.

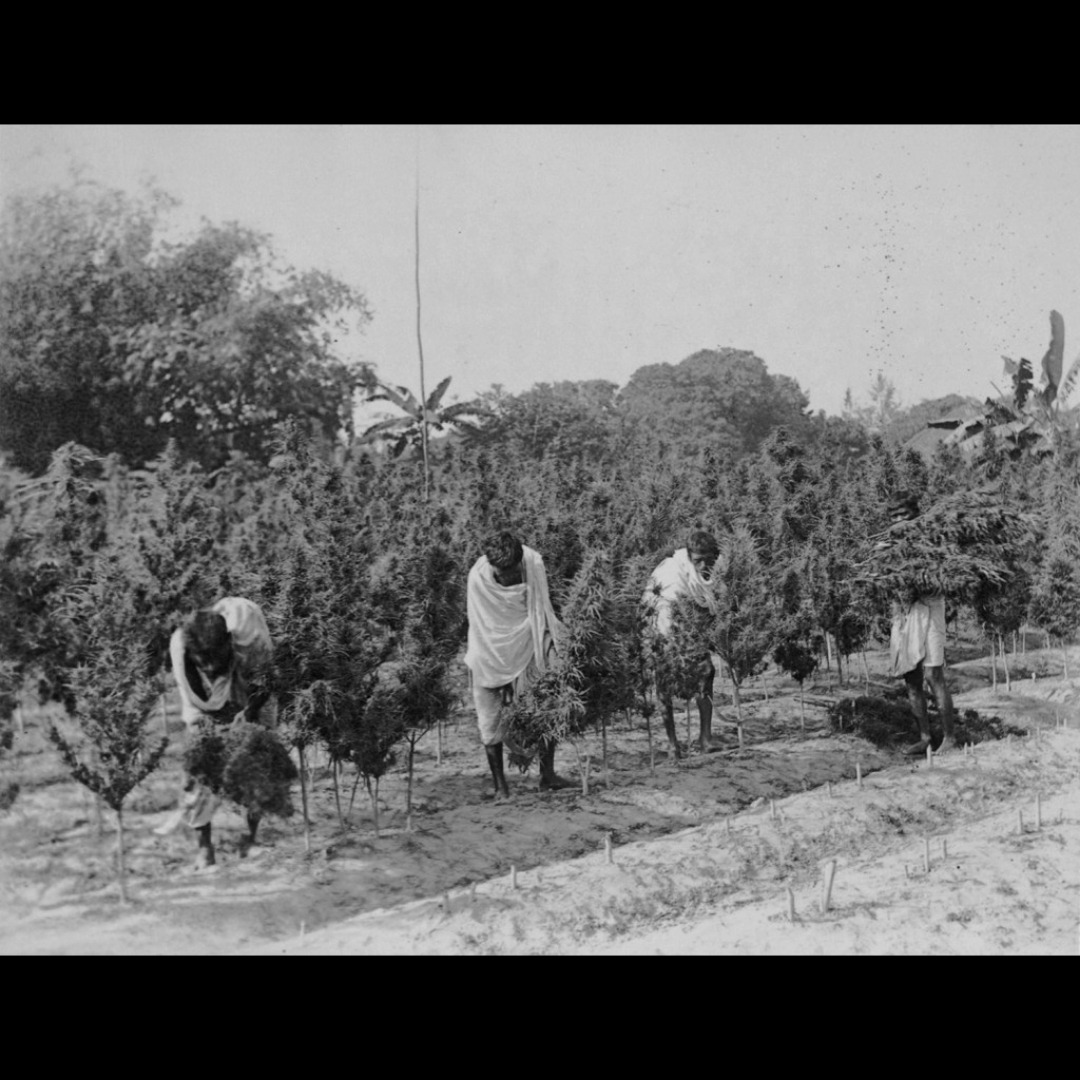

The photograph above is ‘Gathering the Ganja Crop’, shot in Bengal in mid-February 1894 for the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission.

To successfully raise a crop of high-quality, authentic ganja entails skill and know-how, not just seeds of real tropical Sativas – i.e., ganja landraces – though these too are essential.

In historic cultivation centres such as the Ganja Mahal in east Bengal, ganja farming traditionally involved repeated field visits by a specialist ‘ganja doctor’ (poddār), whose task was to identify male and hermaphrodite plants, snapping the offending individuals for later removal by the farmer. To be a ‘ganja doctor’ remained a viable career until as recently as the 1980s in the South Indian state of Kerala.

This 1894 shot of the ganja harvest in Naogaon shows other techniques and factors that were regarded as necessary for getting a ganja landrace to yield a refined product – i.e., pungent, resinous, and potent buds.

Raised beds or ridges (śuli) were prepared on the lightest, best-draining loams available – this ‘terroir’ being highly sought after for ganja. The land was repeatedly ploughed and well manured. One month old seedlings were transplanted from a nursery to these beds around mid-September. The correct timing and extent of the cycles of irrigation and further manuring were crucial.

Harvest commenced around mid-February and went through to mid-March. The point during senescence at which ‘fan leaves’ drop off entirely was and is used as a general indicator that a ganja crop is ready. More important was the loss of chlorophyll, with flowering tops turning to gold or brown hues. Most important of all was that the buds were heavy with resin.

All but the seedling phase of this process takes place outside monsoon. Most of the above points hold true anywhere good ganja is cultivated today in the Asian tropics, particularly in regions such as Thailand, Orissa, and Laos.