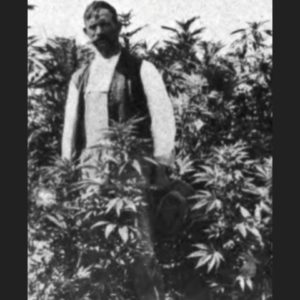

Here’s a c. 1940s shot of a cannabis landrace entitled ‘The Hashish Plant’. The plate is from Egyptian Service: 1902 – 1946 by the British colonial counternarcotics cop Sir Thomas Wentworth Russell, better known as ‘Russell Pasha’. Russell doesn’t specify exactly when or where the photograph was taken, but based on the date of the book and the journeys and hashish trade dynamics he describes, the most likely source seems to be post-WW2 Lebanon.

The morphology is typical of the subsp. indica landrace strains of the Near East, as represented by accessions such as our Lebanese, Syrian, Sinai, and Turkish. All are characterized by semidwarf architecture but generally exhibit markedly narrower leaflet width at maturity than the classic Indica. Phytochemical profiles likewise lack the ‘skunkiness’ of most Central Asian landraces. The same is true of a newly arrived Greek landrace accession, Arcadian.

Collected around Mantineia in the pre-hybrid era, ‘Arcadian’ appears to be descended from the drug-type landrace(s) introduced to the Peloponnese by Levantine hashish smuggling networks in the 1860s following the prohibition of cultivation imposed on Egypt by the imperial Ottoman administration. For another six decades, southern Greece reigned as the world’s preeminent western centre of hashish production, supplying the vast demand from megacities such as Cairo and Alexandria. In the 1920s, Greek government crop eradication efforts driven by the League of Nations shifted the centre of gravity of cultivation back to Syria and Lebanon, a process that was over by the early 1930s.

In the heyday of Greek hashish, the crop employed in districts such as Mantineia was known as ‘kannávi’ and reached just over two metres in height under optimal conditions. Sown in spring, plants commenced flowering around July or August, with harvest done by early October. Essentially the same cycle is followed to this day around the Mediterranean, whether in the mountains of Sinai, southern Turkey, or Bekaa Valley. The final product – ‘hashish’ in the sense of compressed, sieved cannabis resin – was described by Russell as having ‘an oily, heavy smell, like hops’, a lot like contemporary Lebanese. ‘Earthy’, ‘spicy’, ‘rose’, ‘Turkish Delight’, ‘coffee’, ‘caramel’ – these are the types of descriptors most often drawn on by aficionados. Seldom do you encounter ‘skunky’ aromas.

Levantine, Near Eastern, Mediterranean – categorise them how you like, these landraces don’t sit comfortably with the stereotypical ‘Indica’ of western aficionados, who often fudge the ‘vernacular taxonomy’ and classify them as ‘fast, compact Sativas’. They’re no less awkward to fit in the formal taxonomic key for Indicas (subsp. indica var. afghanica) proposed by McPartland and Small.

The USDA field of ‘Kandivi’ – Nevada, c. 1913

By contrast, as you can see from the image immediately above, the landraces employed in the same era in the world’s eastern epicentre of hashish production, Xinjiang or East Turkestan, conform nicely. Collected in the Central Asian desert mountains south of Yarkand in the 1910s by Frank Meyer, this drug-type crop was known to the local Uyghur Turks as ‘kandivi’. As with kannávi in Europe, a central function of the name ‘kandivi’ was to distinguish this crop from the fibre- and seed-type ‘hemp’ landraces also found in China. Cultivated at the USDA station in Nevada around 1914, the plants shown are likely the first Indicas (var. afghanica) to grow in the United States. The government crop scientists noted their ‘skunky odour’. Sadly, the USDA accessions of ‘kandivi’ weren’t maintained and were eventually destroyed. And tragically, Xinjiang itself is now a prison-camp hellscape under the genocidal government of the PRC….