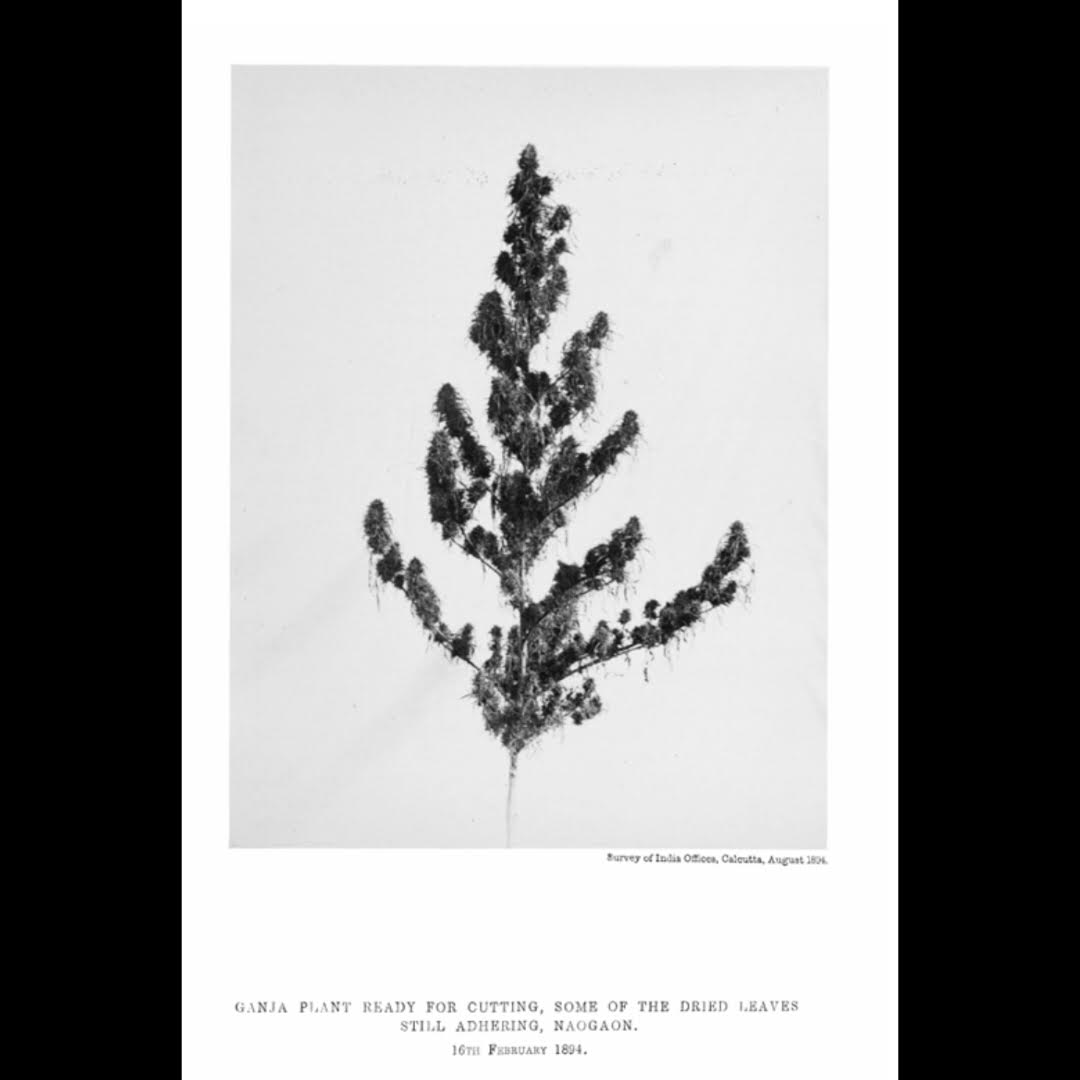

‘Ganja plant ready for cutting, some of the dead leaves still adhering, Naogaon.’ – Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission, 1893-1894

***

The two high-end traditional cannabis drug products are ganja (sinsemilla or ‘semi-sensi’) and charas (resin, either hand-rubbed or dry-sieved). They are produced from landraces. Cannabis landraces are old-school domesticates that are particular to specific regions and products, in this case the charas of the mountains of the Himalaya and desert Central Asia, and the ganja of the tropics and subtropics south of 30° N Latitude.

On 16th February 1894, the above photograph was taken in the Ganja Mahal region of northwest Bengal in what is now the state of Bangladesh. It shows a Bengali ganja landrace ready for harvest. In the informal, underground taxonomy of the modern prohibition era, this plant would be known as a ‘pure Sativa’.

A century earlier than the Commission, in 1785, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck analysed a specimen of East Indian ganja, probably collected south from Bengal on the Coromandel Coast at Pondicherry. He noted the ganja’s strong odour “resembling somewhat that of tobacco” and intoxicating effect: “The principal effect of this plant consists of going to the head, disrupting the brain, where it produces a sort of drunkenness that makes one forget one’s sorrows, and produces a strong gaiety.”

By the late 18th Century, the East Indies ganja trade had come under the control of a violent and dangerously powerful multinational corporation, the East India Company, which operated out of Calcutta and London. The Company profited aggressively from Indians’ taste for cannabis while it ruled and looted India.

At the fin de siècle height of the global cannabis trade, the surveyors of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission took photographs of the ganja fields of Bengal, which are anything but ‘wild’. Tax farmed for every last ounce of revenue, the Ganja Mahal of Bengal was now a focus of the masters of the Victorian Raj, the successors of the East India Company, mainly because these British imperialists were looking to improve cultivation techniques to raise crop yields – and also to prevent smuggling, which was thriving across India’s mountain and desert frontiers and through its extensive internal jungle and river networks such as the Northeast Frontier Tracts.

You can learn about the East India Company here and in William Dalrymple’s great book, The Anarchy: