Here’s Professor James Mills, arguably the most authoritative historian of cannabis, with a quick tour of the first of his two books on the little-known role of the British Empire in the Asian cannabis trade: Cannabis Britannica: Empire, Trade, and Prohibition.

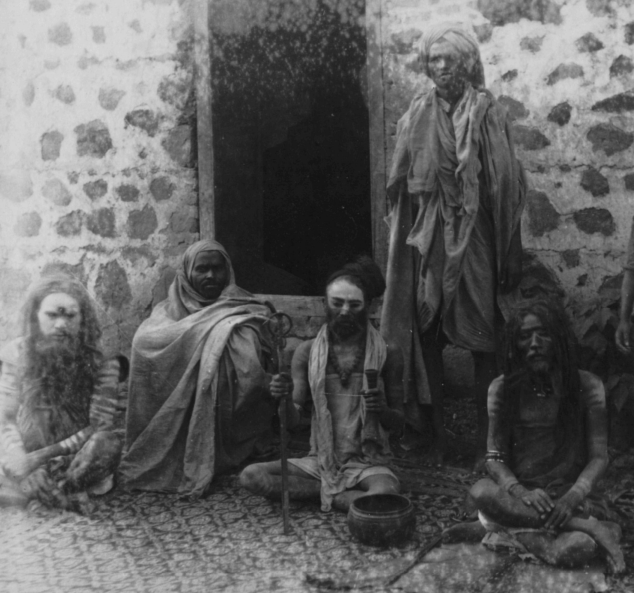

The featured image is a detail from of a photo from the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission entitled ‘Group of Gosavis, Habitual Excessive Ganja Smokers, Kandesh’.

***

Tracing the name ‘Gosavi’ (gōsāvī: गोसावी) to its original bearers leads to a realm of Indian cannabis culture that remains hidden from view for most aficionados in the west – a history of drug-fuelled resistance to tyranny and empire, one in which proponents and opponents of cannabis all understood the power of this plant to both inspire and enable rebellion.

Like ‘bairagi’ or ‘fakir’, ‘gosavi’ is one of a wide range of loose terms used in South Asia to refer to wandering yogis, many of who continue to earn reputations for being chronic ‘habitual excessive ganja smokers’, but who in their various incarnations in the landscape of medieval and early modern India morphed from solitary pilgrims to bands of vagabonds, to guilds of networked merchants, to mercenaries or warlords at the head of powerful armies of 50,000 or more fighters.

In their heyday – up until around the late eighteenth century – groups such as Gosavis, Gosains, Bairagis, Sannyasis, and Malangs roamed freely across India, particularly in the northern regions from the Punjab to Bengal, usually in bands, and were often not just heavily stoned but heavily armed. Predictably, their reputations were checkered.

For most aficionados, ganja and dreadlocked Indian yogis immediately call to mind notions of pacifism and non-violence rather than warrior-saints or plundering vagabonds. But this tells us much more about the western stereotypes of Oriental spiritual cannabis use forged in the days of the Hippie Trail than it does about figures such as Gosavis themselves or the uses to which they put cannabis, among the chief of which was as a battle draught and – equally significant in the roving lifestyle of a warrior or vagabond – a tonic and a medicine.

Across India, warrior ascetics from Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh origins were famed not just among Indians themselves but among European colonists for their formidable accomplishment in martial arts – and most of all for their lethality in close combat. With this came skill in guerilla warfare that was legendary, not merely hit-and-run tactics but strategies built around the ability of bands or units to move at astonishing speed through all terrains, including hill and jungle, far outpacing imperial armies. Cannabis was an integral part of this nomadic martial mode of existence, enabling fighters to cope with the challenges of physical ware and fatigue, as well as bringing benefits such as steadying the hands of archers.

In the Punjab, rebellions against the oppressive rule of the Mughal Empire or Hindu Hill Rajas were led by Sikh federations such as the Bhangi Misl – who took their name from their prolific intake of cannabis (bhang) on and off the battlefield, most notoriously by their ascetic elite fighters, the Nihangs.

But uprisings by warrior ascetics against oppressive regimes slowed with the suppression of the wilder, more nomadic and martial lineages under the colonial rule of the East India Company, when Governor Warren Hastings responded ruthlessly to the Sannyasi and Fakir Rebellions. British accounts of going up against Sannyasis and Sikhs in battle during this period are full of references to their opponents’ battlefield use of cannabis.

Not long after the Sannyasi Rebellions, the Company itself nevertheless entered a strategic alliance against Indian states with the yogi warlord Anoop Giri Gosain. At the peak of his power, Anoop Giri ruled crucial swathes of Central India and could make or break a Maharaja or Sultan – but found he shared more in common with the Company, a corporation of upstart outsiders, and so sealed the fate of warrior ascetics and – indeed – of India….

More of this history can be found in The Anarchy: The East India Company, Corporate Violence, and the Pillage of an Empire and Warrior Ascetics and Indian Empires.